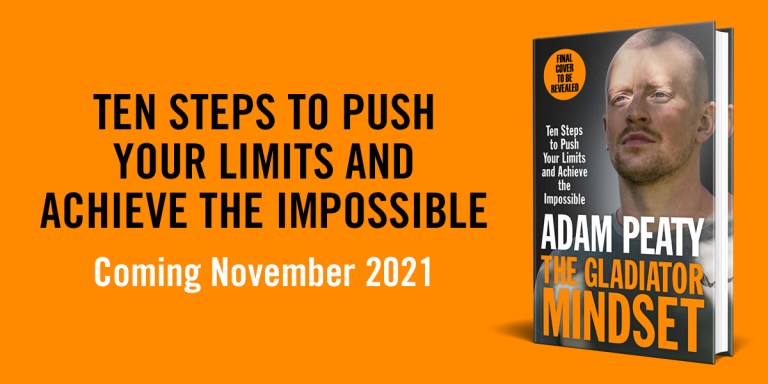

Exclusive extract: A Winter Grave by Peter May

In 2051, when a young meteorologist discovers a body entombed in ice, Glasgow detective Cameron Brodie sets out on a hazardous journey to the isolated and ice-bound village of Kinlochleven. Read this exclusive extract from Peter May’s masterful thriller A Winter Grave.

The rain was mixed with hail, turning to ice as it hit frozen ground and making conditions treacherous underfoot. Such little light penetrated the thick, sulphurous cloud that smothered the city, it would have been easy to mistake mid-morning for first light.

Overhead electric lights burned all the way along the corridor, making it seem even darker outside, and turning hard, cream-painted surfaces into reflective veneers that almost hurt the eyes. Brodie glanced from the windows as he strode the length of the hall. The river was swollen again and seemed sluggish as the surge from the estuary slowed its seaward passage.

The DCI’s door stood ajar. Brodie could hear the distant chatter of computer keyboards and a murmur of voices from further along. They invoked a sense of hush that he was reluctant to break and he knocked softly on the door.

The voice from beyond it demonstrated no such sensitivity. ‘Enter!’ It was like the crack of a rifle.

Brodie stepped in, and Detective Chief Inspector Angus Maclaren glanced up from paperwork that lay like a snowdrift across his desk. He was in shirtsleeves, his tie loose at the neck, normally well-kempt hair falling in a loop across his forehead. He swept it back with a careless hand. ‘You like a bit of hillwalking, I’m told, Brodie. Bit of climbing. That right?’ There was a hint of condescension in his tone, incredulity that anyone might be drawn to indulge in such an activity. Not least one of his officers.

Born four years before the turn of the millennium, Brodie had worked his way up through the force the hard way. Graduating from Tulliallan, and spending more than ten years in uniform before sitting further exams and embarking on his investigator pathway, gaining entrance finally to the criminal investigation department as a detective constable. Two promotions later, he found himself serving under a senior officer twenty-five years his junior, who had fast-tracked his way directly to detective status as a university graduate with a degree in criminology and law from the University of Stirling. A senior officer who had little time for Brodie’s old school approach. And even less, apparently, for his passion for hillwalking.

‘Yes, sir.’

It was his widowed father, an unemployed welder made redundant from one of the last shipyards on the Clyde, who had taken him hillwalking for the first time in the West Highlands. Brodie had only been fourteen when they took the train from Queen Street up to Arrochar to climb The Cobbler, ill-dressed and ill-equipped. The right gear cost money, and his father had precious little of the stuff. But that first taste of the wild outdoors gave Brodie the bug, and as he grew more experienced, and began to earn, he started taking safety more seriously, spending all his spare time haunting sports equipment shops in the city. He was devastated when his father was struck down by a stroke. Semi-paralysed, he died a year later when Brodie was just twenty-one. And Brodie’s weekend trips to the hills and mountains of the Highlands became something of an obsession, an escape from a solitary life. And in recent years, an escape from life itself.

Maclaren pushed himself back in his chair and regarded the older man speculatively. ‘Remember those stories in the papers about three months ago? Scottish Herald reporter going missing in the West Highlands?’

Brodie didn’t. ‘No, sir.’

Maclaren tutted his annoyance and pushed an open folder of newspaper cuttings towards him. The Herald itself, the Scotsman, the Record. Most of the other national papers had gone to the wall. Apart from these, and a handful of surviving local newspapers, most people got their news from TV, internet and social media. ‘A modern police officer needs to keep himself abreast of current affairs, Brodie. How can we police a society in ignorance of them?’

Brodie supposed that the question was rhetorical and maintained a silence that drew a look from Maclaren, as if he suspected dumb insolence.

‘Charles Younger,’ he said. ‘The paper’s investigative reporter. Specialised in political scandals. Last August he went hillwalking in the Loch Leven area, even though by all accounts he’d never been hillwalking in his life. Went out one day, never came back. No trace of him ever found. Until now.’ He paused, as if waiting for Brodie to ask. When he didn’t, the DCI sighed impatiently and added, ‘Younger’s body was discovered frozen in a snow patch in a north-facing corrie of Binnein Mòr, above the village of—’

Brodie interrupted for the first time. ‘I know where Binnein Mòr is. I’ve climbed most of the mountains in the Kinlochleven area.’

‘Aye, so I heard. All of the Munros in the Mamores, I believe.’

Brodie offered a single nod in affirmation.

‘I want you to go up there and check it out.’

‘Why are Inverness not dealing with it?’

‘Because the two officers they sent to investigate were killed when their drone came down in an ice storm. Edinburgh have asked us to send someone instead. And I’m asking you.’

***

A Winter Grave is coming in January 2023. Pre-order your copy.